Chacha20-Poly1305

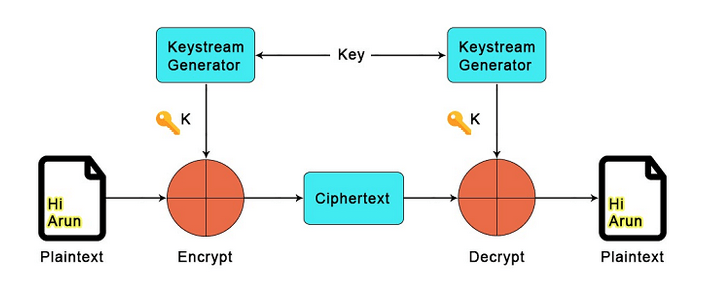

ChaCha20-Poly1305 architecture consists of two main components, the stream cipher ChaCha20 and the authentication mechanism Poly1305 by the same author D.J. Berstein. The two building blocks of the construction, the algorithms Poly1305 and ChaCha20, were both independently designed, in 2005 and 2008.

Algorithm

Chacha20

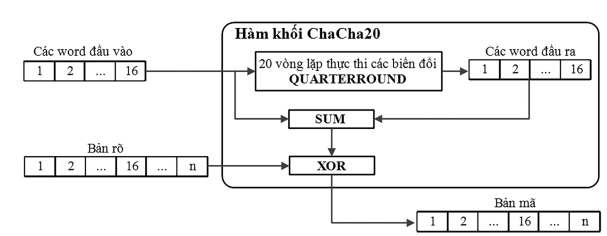

The ChaCha20 algorithm uses ChaCha20 block functions to generate the encryption keystream.

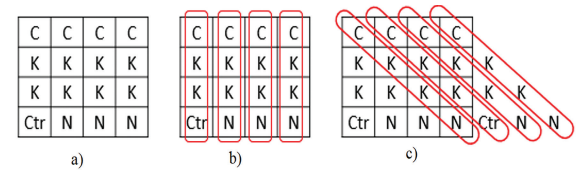

The input of the ChaCha20 block function is a 4x4 word matrix described as in this figure:

More details in figure a are 128 bit constant C (4-word), 256 bit key K (8-word), 32 bit counter parameter Ctr (1 word), 96 bit nonce N (3 words). Then perform 20 loops alternatingly executing the column round transformations according to figure b and the diagonal round transformations according to figure c.

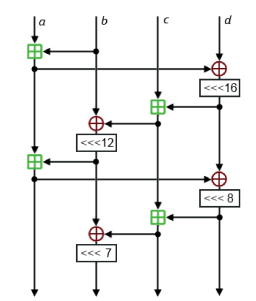

These two circular shifts are implemented by a single QUARTERROUND transformation (cross or column shift based on the input index to the QUARTERROUND function) as shown in this:

def chacha20_quarter_round(a,b,c,d):

a = (a + b) & 0xFFFFFFFF

d ^= a; d = ((d << 16) & 0xFFFFFFFF) | (d >> 16)

c = (c + d) & 0xFFFFFFFF

b ^= c; b = ((b << 12) & 0xFFFFFFFF) | (b >> 20)

a = (a + b) & 0xFFFFFFFF

d ^= a; d = ((d << 8) & 0xFFFFFFFF) | (d >> 24)

c = (c + d) & 0xFFFFFFFF

b ^= c; b = ((b << 7) & 0xFFFFFFFF) | (b >> 25)

return a,b,c,d

In 20 loops, each loop performs 8 operations QUARTERROUND and the order is: QUARTERROUND from 1 to 4 performs column rotation, while QUARTERROUND from 5 to 8 performs cross rotation. The output of the 20-loop block is 16 words, which are added to the 16 input words modulo $2^{32}$ to generate 16 key words. The 16 key words are XORed with the 16 plaintext words to obtain 16 ciphertext words.

def chacha20_block(key32: bytes, counter: int, nonce12: bytes) -> bytes:

def u32(b): return struct.unpack("<I", b)[0]

state = [

0x61707865, 0x3320646e, 0x79622d32, 0x6b206574,

u32(key32[0:4]), u32(key32[4:8]), u32(key32[8:12]), u32(key32[12:16]),

u32(key32[16:20]), u32(key32[20:24]), u32(key32[24:28]), u32(key32[28:32]),

counter & 0xFFFFFFFF,

u32(nonce12[0:4]), u32(nonce12[4:8]), u32(nonce12[8:12])

]

x = state.copy()

for _ in range(20):

# column rounds

x[0],x[4],x[8],x[12] = chacha20_quarter_round(x[0],x[4],x[8],x[12])

x[1],x[5],x[9],x[13] = chacha20_quarter_round(x[1],x[5],x[9],x[13])

x[2],x[6],x[10],x[14] = chacha20_quarter_round(x[2],x[6],x[10],x[14])

x[3],x[7],x[11],x[15] = chacha20_quarter_round(x[3],x[7],x[11],x[15])

# diagonal rounds

x[0],x[5],x[10],x[15] = chacha20_quarter_round(x[0],x[5],x[10],x[15])

x[1],x[6],x[11],x[12] = chacha20_quarter_round(x[1],x[6],x[11],x[12])

x[2],x[7],x[8],x[13] = chacha20_quarter_round(x[2],x[7],x[8],x[13])

x[3],x[4],x[9],x[14] = chacha20_quarter_round(x[3],x[4],x[9],x[14])

out = b"".join(struct.pack("<I", (x[i] + state[i]) & 0xFFFFFFFF) for i in range(16))

return out

Poly1305

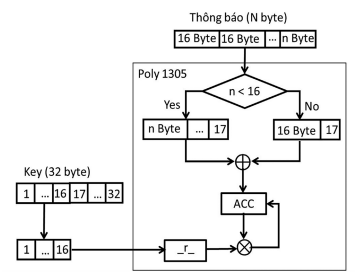

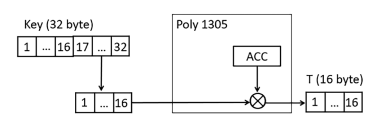

Poly1305 is a message authentication cipher (MAC) to ensure the authenticity and integrity of data. The input key is divided into 2 parts called r and s, each part is 128 bits long. The pair (r,s) must be unique and unguessable for each call.

The input message is divided into 16-byte blocks (the last block can be padded with 0 bits), the 16-byte blocks are padded with 1 byte with value 0x01 to 17 bytes, calculations are performed on these blocks with r on the Z() field to create an accumulator.

Finally the value s is added to the accumulator and the 128 bits are extracted as the authentication tag.

def _clamp_r(r_bytes: bytes) -> int:

"""Convert 16-byte little-endian r_bytes to integer and apply clamp per RFC."""

if len(r_bytes) != 16:

raise ValueError("r must be 16 bytes")

r = int.from_bytes(r_bytes, "little")

# clamp mask: r &= 0x0ffffffc0ffffffc0ffffffc0fffffff

# expressed as integer:

clamp_mask = 0x0ffffffc0ffffffc0ffffffc0fffffff

return r & clamp_mask

def poly1305_mac(msg: bytes, key: bytes) -> bytes:

"""

Compute Poly1305 tag for message `msg` using 32-byte one-time key `key` (r||s).

Returns 16-byte tag.

"""

if len(key) != 32:

raise ValueError("Poly1305 key must be 32 bytes")

r_bytes = key[:16]

s_bytes = key[16:32]

r = _clamp_r(r_bytes)

s = int.from_bytes(s_bytes, "little") # s added at the end

acc = 0

# Process message in 16-byte blocks

offset = 0

while offset < len(msg):

block = msg[offset:offset + 16]

offset += len(block)

# n = int.from_bytes(block, 'little') + (1 << (8*len(block)))

# append the 1 byte in little-endian domain:

n = int.from_bytes(block + b'\x01', "little")

acc = (acc + n) % P130

acc = (acc * r) % P130

# Final tag = (acc + s) mod 2^128

tag_int = (acc + s) % (1 << 128)

tag = tag_int.to_bytes(16, "little")

return tag

Here is the implement of this algorithm: Link

Security

ChaCha20-Poly1305 is generally secure and offers better resistance to timing attacks than AES-GCM. However, like GCM, its security relies strictly on unique nonces. While specific implementations like SSH face vulnerabilities such as the Terrapin attack, this post focuses on a fundamental flaw: exploiting ChaCha20-Poly1305 under nonce reuse.

First of all, I will create a challenge named chall.py to generate 2 pairs of (ct, tag) using a known plaintext. This allows us to recover the keystream and eventually forge a tag for a new message.

In a typical oracle scheme, while the secret key is reused across multiple messages, the nonce must remain unique. However, if the Nonce is inadvertently reused, the Poly1305 one-time key pair $(r, s)$ remains identical for those messages. If we capture two distinct pairs of (ct, tag) generated from the same $(r, s)$, we can set up the following system of equations:

$$tag_1 = \text{Poly1305}(r, s, m_1) = (P_1(r) \pmod p) + s \pmod{2^{128}}$$$$tag_2 = \text{Poly1305}(r, s, m_2) = (P_2(r) \pmod p) + s \pmod{2^{128}}$$$\text{where } p = 2^{130} - 5, P_j(r)=\sum\text{block}_{j, i} \cdot r^i \pmod p$

By subtracting one equation from the other, we can eliminate the unknown scalar $s$. However, because the final addition of $s$ is performed modulo $2^{128}$, while the polynomial evaluation is modulo $2^{130}-5$, we must account for the modular difference. This results in the following polynomial equation:

$$tag_1 - tag_2 = \sum (\text{block}_{1,i} - \text{block}_{2,i}) \cdot r^i + k \cdot 2^{128} \pmod p$$Here, $k$ represents the “carry” difference resulting from the modulo $2^{128}$ addition, typically falling within the range $k \in \{-4, \dots, 4\}$.

def make_poly(data):

padded = data + b'\x00' * ((16 - len(data) % 16) % 16)

msg = padded + (0).to_bytes(8, 'little') + len(data).to_bytes(8, 'little')

coeffs = [to_int(msg[i:i+16] + b'\x01') for i in range(0, len(msg), 16)]

return sum(c * r_sym**(len(coeffs)-i) for i, c in enumerate(coeffs))

poly_diff = make_poly(c1) - make_poly(c2)

delta_tag = t1 - t2

r, s = None, None

for k in range(-5, 6):

roots = (poly_diff - (delta_tag + k * 2**128)).roots()

for r_val, _ in roots:

r_int = int(r_val)

if clamp_check(r_int):

val_poly1 = int(make_poly(c1)(r_int))

s_cand = (t1 - val_poly1) % 2**128

val_poly2 = int(make_poly(c2)(r_int))

if (t2 - val_poly2) % 2**128 == s_cand:

r, s = r_int, s_cand

break

if r: break

Recovering the Key: By iterating through the small range of possible $k$ values, we can solve for the roots of this polynomial to find potential candidates for $r$. The correct $r$ can be identified by verifying it against the specific formatting rules of the Poly1305 “clamp” function. Once $r$ is found, we can trivially derive $s$ from either original tag. With the complete $(r, s)$ pair, we can now forge valid tags for any arbitrary message.

All of the code I put in here

RC4

RC4 (also known as ARC4 or ARCFOUR, meaning Alleged RC4) is a stream cipher. While it is remarkable for its simplicity and speed in software, multiple vulnerabilities have been discovered in RC4, rendering it insecure. RC4 is a stream cipher designed by Ronald Rivest of RSA Security in 1987.

Algorithm

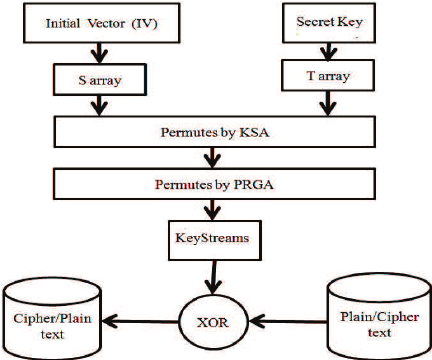

To generate the keystream, the cipher makes use of a secret internal state which consists of two parts:

- A permutation of all 256 possible bytes (denoted “S”).

- Two 8-bit index-pointers (denoted “i” and “j”).

The permutation is initialized with a variable-length key, typically between 40 and 2048 bits, using the key-scheduling algorithm (KSA). Then using the pseudo-random generation algorithm (PRGA) to generate keystream.

Key-Scheduling Algorithm (KSA)

Let $S$ be a state array of size $N=256$ and $K$ be the secret key array of length $L$ bytes, where $1 \le L \le 256$.

- Initialization (Identity Permutation) $$\forall i \in \{0, \dots, N-1\}: S[i] \leftarrow i$$

- KSA Scrambling Loop

Let $j \leftarrow 0$. For $i$ from $0$ to $N-1$:

$$j \leftarrow (j + S[i] + K[i \bmod L]) \bmod N$$$$\text{Swap}(S[i], S[j])$$Observation on Key Equivalence: Due to the modulo operator $i \bmod L$, the key $K$ functions as a circular buffer.

def rc4_ksa(key: bytes):

keylen = len(key)

S = list(range(256))

j = 0

for i in range(256):

j = (j + S[i] + key[i % keylen]) & 0xFF

S[i], S[j] = S[j], S[i]

return S

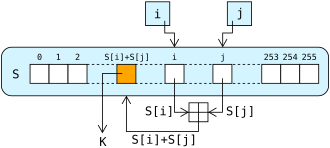

Pseudo-Random Generation Algorithm (PRGA)

Let $S$ be the permutation state array of size $N=256$ and $i, j$ be indices initialized to $0$.

For each byte $k$ required:

$$\begin{aligned} i &\leftarrow (i + 1) \bmod N \\ j &\leftarrow (j + S[i]) \bmod N \\ S &\leftarrow \text{Swap}(S[i], S[j]) \\ t &\leftarrow (S[i] + S[j]) \bmod N \\ K_k &\leftarrow S[t] \end{aligned}$$Since the index $i$ increments deterministically ($i \leftarrow i + 1$), so:

$$\forall x \in \{0, \dots, 255\}, \text{the element } S[x] \text{ is swapped at least once per } 256 \text{ rounds.}$$This ensures that the permutation $S$ continues to evolve significantly throughout the keystream generation, rather than settling into a short cycle.

def rc4_prga(S):

i = 0

j = 0

while True:

i = (i + 1) & 0xFF

j = (j + S[i]) & 0xFF

S[i], S[j] = S[j], S[i]

K = S[(S[i] + S[j]) & 0xFF]

yield K

Here is the implement of this algorithm: Link.

Security

Unlike a modern stream cipher, RC4 does not take a separate nonce alongside the key. This means that if a single long-term key is to be used to securely encrypt multiple streams, the protocol must specify how to combine the nonce and the long-term key to generate the stream key for RC4.

While it is remarkable for its simplicity and speed in software, multiple vulnerabilities have been discovered in RC4. Particularly problematic uses of RC4 have led to very insecure protocols such as WEP.

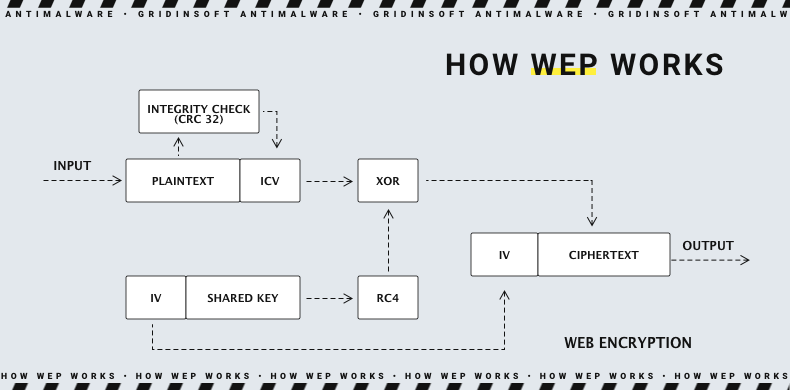

Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP) was included as the privacy component of the original IEEE 802.11 standard ratified in 1997. WEP uses the stream cipher RC4 for confidentiality, and the CRC-32 checksum for integrity.

Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP) was included as the privacy component of the original IEEE 802.11 standard ratified in 1997. WEP uses the stream cipher RC4 for confidentiality, and the CRC-32 checksum for integrity.

However, RC4’s weak key schedule then gives rise to related-key attacks, like the Fluhrer, Mantin and Shamir attack.

Fluhrer, Mantin and Shamir attack

The basis of the FMS attack lies in the use of weak initialization vectors (IVs) used with RC4.

When the WEP security standard was designed for WiFi in the 90s, engineers specified the following key structure: IV length is fixed at 24 bits (3 bytes) and session key is the result of the concatenation of the IV and the Root Key together.

Therefore, the Root Key will start at index 3 so if we want to recover the Root Key, we could start at this index. After a few calculation, we choose $(i, 255, x)$ as the weak IV with i is the index of the bytes we want to recover, x is an arbitrary integer number.

For example, we set i = A + 3. Assuming length of the Root Key smaller than 256. The key now is: [A + 3, 255, x, rk[0], rk[1],…]

Here are some of the first rounds as we process the KSA:

- Round 1:

- Start with S:

+-----------------------------------------------+

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ... | 255 |

+-----------------------------------------------+

^

i,j

- Calculate:

j = (j + S[i] + key[i % keylen]) & 0xFF = (0 + S[0] + key[0]) & 0xFF = (0 + 0 + A + 3) % 255 = A + 3

Swap S[0] and S[A + 3]: S[0] = A + 3, S[A + 3] = 0

- S becomes:

+--------------------------------------------+

| A + 3 | 1 | 2 | ... | 0 | ... | 255 |

+--------------------------------------------+

^ ^

i j

- Round 2:

- Start with S:

+--------------------------------------------+

| A + 3 | 1 | 2 | ... | 0 | ... | 255 |

+--------------------------------------------+

^ ^

i j

- Calculate:

j = (j + S[i] + key[i % keylen]) & 0xFF = (A + 3 + S[1] + key[1]) & 0xFF = (A + 3 + 1 + 255) % 256 = A + 3

Swap S[1] and S[A + 3]: S[1] = 0, S[A + 3] = 1

- S becomes:

+--------------------------------------------+

| A + 3 | 0 | 2 | ... | 1 | ... | 255 |

+--------------------------------------------+

^ ^

i j

- Round 3:

- Start with S:

+--------------------------------------------+

| A + 3 | 0 | 2 | ... | 1 | ... | 255 |

+--------------------------------------------+

^ ^

i j

- Calculate:

j = (j + S[i] + key[i % keylen]) & 0xFF = (A + 3 + S[2] + key[2]) & 0xFF = (A + 3 + 2 + x) % 256 = X,

with X = (x + A + 5) % 256

Swap S[2] and S[X]: S[2] = X, S[X] = 2

- S becomes:

+-----------------------------------------------------------+

| A + 3 | 0 | X | 1 | 4 | 5 | ... | 2 | ... | 255 |

+-----------------------------------------------------------+

^ ^

i j

- Round 4:

- Start with S:

+-------------------------------------------------------------+

| A + 3 | 0 | X | 1 | 4 | 5 | ... | 2 | ... | 255 |

+-------------------------------------------------------------+

^ ^

i j

- Calculate:

j = (j + S[i] + key[i % keylen]) & 0xFF = (X + S[3] + key[3]) & 0xFF = (X + 1 + rk[0]) % 256 = Q,

with Q = (X + 1 + rk[0]) % 256 = (x + A + 6 + rk[0]) % 256

Swap S[3] and S[Q]: S[3] = Q, S[X] = 1

- S becomes:

+-------------------------------------------------------------+

| A + 3 | 0 | X | Q | 4 | 5 | ... | 1 | ... | 255 |

+-------------------------------------------------------------+

^ ^

i j

Then continue until A + 3 rounds and if this still has S[0] = A + 3, S[1] = 0, it could lead to the first bytes of the keystream after PRGA is:

$$K[0] = S[S[1] + S[S[1]] = S[0+S[0]]=S[3] =Q$$We can recover the byte with index A of the Root Key:

When I calculate the probability of the case $Q = j_{A+4}$, it came out to be 5% compared to the normal $\dfrac{1}{256}$ because of my chosen weak IV. The probability that a value will not be touched in a random loop is approximately $1-\dfrac{1}{256}$ and survives 256 rounds is $(1-\dfrac{1}{256})^{256}=e^{-1}$. Finally, we require three specific values ($S[0], S[1]$, and the target) to remain unmoved, the combined probability is derived as $(e^{-1})^3 = e^{-3} \approx 0.0497$.

S = list(range(256))

j = 0

for i in range(A + 3):

j = (j + S[i] + key[i % len(key)]) % 256

S[i], S[j] = S[j], S[i]

if i == 1:

o0, o1 = S[0], S[1]

i = A + 3

if S[1] < i and (S[1] + S[S[1]]) == i:

if o0 != S[0] or o1 != S[1]:

continue

key_byte = (ks - j - S[i]) % 256

probs[key_byte] += 1

From there, we count each case x to see which value appears most often and determine that it is the one we are looking for.

The implement, challenge and also the solution I put in here.